(...all images from VLISCO...)

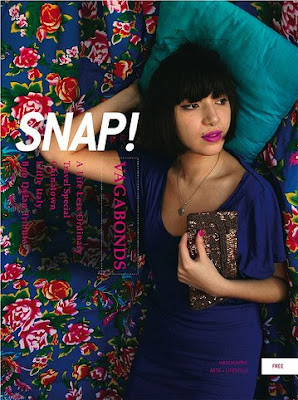

(...all images from VLISCO...)I have always had a great interest in African textile prints. I have a couple of dresses scooped up from the Salvation Army stored safely away in the back of a closet in Montreal and I have bought another one and some meters of fabric since being here in New York. The patterns are so bright and alive - I love seeing them poke out from the bags and boxes I have stuffed them in for now. I would really like to make a skirt or a bag, or just something out of them, it has been on my list of things to do for years now. Someday.I was reminded of these fabrics when I opened an email the other day from MaryAnne Mathias (of Hastings + Main fame), about her new project Osei-Duro, a collection of socially responsible and sustainable clothing that encourages international/intercultural cooperation. Their blog is full of great examples of beautiful batiks. This week I also came across this very interesting article which I poached off of the fantastic tumble blog 2THEWALLS - so thanks to both of these individuals very much for the inspiration (and fodder) to do this post. *

Lomé, Togo-- The crowd on the Rue du Grand Marché is packed solid. You have to dodge and weave to make any progress, threading your way past stalls piled high with dried fish, cassette tapes, butchered goats, toothpaste, and cheap steel frying pans. Your field of vision is confused: too many different objects, patterns, colors. You're surrounded by women in traditional dresses of fantastically complicated fabric--intricate, vivid designs layered in folds you can't quite decipher the workings of. This is the Africa you came to see, the real Africa, just like it looks in those documentaries on the Discovery Channel. You penetrate deeper into the market, duck into a cavernous concrete building full of vegetable and fruit vendors, climb the stairs. You are in the hall of fabric merchants. You move through stacks of shimmering cloth and blazing colors leap out at you from all sides. This is the authentic stuff--not the cheap imitation junk sold at the hotel tourist traps, but the real thing, the fabric African women prize most highly for traditional dress, recognizable by the legend printed along the border: Veritable Wax Hollandais.

"Hollandais"?

It seems the batik, or wax-print, fabrics that are so indispensable to West African traditional dress are not, by and large, actually from Africa. The most coveted, the ones that set the trends, are designed and manufactured in the Netherlands, in the nondescript factory town of Helmond, by the Vlisco corporation. And this is nothing new. The Dutch, and Vlisco in particular, have dominated the African print-fabric market since the end of the nineteenth century.

"Vlisco was founded in 1846 by a famous Dutch merchant family called the van Vlissingens," explains Joop van der Meij, the company's CEO. "One of the van Vlissingen sons had been in Indonesia, where he discovered the batik method of dying cloth. He had the idea that maybe this method could be industrialized in Europe." By the late 1800s Dutch factories were supplying the bulk of the Indonesian batik market, and as Dutch freighters stopped at various African ports on their way over, the fabrics began to gain an African clientele. At the beginning of the twentieth century, when measures were taken to protect domestic Indonesian batik production, the market for imports there slumped. Africa gradually became the exclusive market for Dutch batik, and by the 1960s Vlisco, having merged with all its rivals, had become the exclusive supplier.

In an industry where the reverse is more common, Vlisco is an anomaly: a European-based textile company whose market is in the third world. Almost none of Vlisco's product is bought in Europe or North America. "Anything we could design for the European market, the Asians can produce for a fraction of the price," van der Meij explains. It's only in Africa, where Real Dutch Wax carries the authority of a brand like Rolls-Royce or Rolex, that consumers care about the difference between Vlisco quality and cheap Asian imitations.

And Vlisco guards its qualitative edge jealously. Industrial batik is a complex process. Patterns are printed in wax on long strips of cloth, which are then immersed in vats of dye, usually indigo. The parts of the cloth not covered in wax absorb the dye, laying down a basic pattern. The wax-printed fabric can be sent through machines that partially break off the wax; since the wax breaks arbitrarily, no two lengths of the cloth are quite alike, which is what gives wax-print fabric its characteristic organic richness. Then the fabric is pattern-printed with other colors, anywhere from one to three times.

The trickiest part comes in trying to align patterns in different colors. For example, wax printing makes it very difficult to lay down the outline of a rose in indigo, and then fill it in with red. Usually the colors don't line up properly, and it comes out looking like bad offset printing. On Vlisco fabrics, however, the colors line up right. The company keeps its alignment process top secret; the building in the Helmond plant where it takes place is off-limits to outsiders. It is this process, along with nonbleeding dyes and high-quality cotton, that justifies the tremendous difference in price between Real Dutch Wax and its competition.

Out on the street in Lomé, that competition is pressing hard, as Madame Rose Creppy can attest. Madame Creppy is the president of Lomé's association of market women, and for 40 years, she's been selling nothing but Real Dutch Wax at her stall in the grand marché. Top-level market women like Madame Creppy are known in West Africa as "Nana-Benzes," after their penchant for driving Mercedes, and Creppy certainly fits the bill. A substantial woman in gold-framed eyeglasses, gold necklace, and gold wristwatch--swathed in indigo Dutch Wax from head to toe--she's clearly used to turning a profit. But lately business has been bad. "No one can afford to buy the real thing," she sighs. "Instead they buy Sosso brand, made in Pakistan. The colors fade the first time you wash it."

The quality may be lower, but the price argument is persuasive in a country like Togo, where per-capita annual income hovers around $350 per year. Real Dutch Wax goes for as much as 70,000 CFA francs (or about $90) for a length of six meters; the Asian imitations, which bear amusingly deceptive logos like "Real Wax--Printed as Holland," sell for 6,000 to 7,000 CFA francs. With the worsening economic situation in much of West Africa--stagnation in postcoup Ivory Coast, Ghana's unstable currency, the catastrophic implosion of Congo during the past two years--Vlisco has seen its profits shrink. It reported net turnover of $167 million in 1999, down from $203 million in 1998.

The patterns on the imitation fabrics, meanwhile, are often nearly identical to those on Real Dutch Wax, because the competitors steal them. Van der Meij claims that 80 percent of the designs one sees on wax-print fabrics in Africa started out on Vlisco drawing boards. The company has fought several successful legal actions, but the Asians are not to be deterred. Lately Nigerian textile makers have also been getting in on the act. "We can put the new fabrics out on the market as soon as the containers arrive from Holland," says Agbobli Médémé, service representative of Vlisco's Togolese partner company, V.A.C.-Togo. "The Nigerian copies start showing up eight days later."

So the authentic traditional West African fabrics are the ones produced in Holland, and the stuff made in West Africa is fake? Can this be right?

Not entirely. Vlisco's parent company, Gamma Holdings, does have West African subsidiaries--GTP in Ghana, Uniwax in Ivory Coast--that manufacture high-quality, original-print fabrics. But those companies are not privy to Vlisco's secret wax technologies, so they don't produce the jealously guarded Veritable Wax Hollandais. More important, nearly all of the new designs are created at Vlisco's headquarters in Helmond, and most of the designers there are Dutch--not one of them is African.

Can a bunch of Dutch designers really stay ahead of the curve of West African fashion? Vlisco thinks so. Van der Meij points to the success of the Gamma companies' joint launch of their 2000 line of fabrics at a fashion show last fall in Abidjan. And both he and Médémé stress the importance of the feedback the company gets from important buyers like Madame Creppy, who can let them know what's selling and what isn't. Creppy confirms that she helped quash a line of fabrics depicting people dancing and musicians playing. "Nobody wanted to buy those things," she says. Why not? "They weren't any good," she explains, convincingly, if a bit opaquely.

And what's hip right now? What are the youth of Lomé wearing this season--the ones who can afford it, anyway? Madame Creppy sighs. Nothing is in fashion, she says. No one is buying.

But if you drop by Madame Creppy's stall while she's out and talk to her 20-year-old daughter Sivomey, you'll hear a somewhat more optimistic story. Sivomey has been working her mother's stall for the last two years. She loves it; there's nothing she'd rather do for a living. Asked what the kids are into these days, Sivomey quickly pulls down a pair of matrixlike, high-tech fabrics in almost fluorescent hues. They don't look entirely different from what's hot in Amsterdam. "This green is chic," says Sivomey. "And this yellow. Bright, sharp colors. Tout ce qui eflash.' Whatever flashes."

Like Sivomey, van der Meij keeps the bright spots in mind when contemplating Vlisco's future. He is circumspect about the company's strategies for handling the volatile market, saying only, "We are not pessimistic about the future. We believe that West Africa has to settle and accept the new tax regime, and to wait for the elections in Ivory Coast." Other signs of hope are emerging: Senegal and Nigeria have recently accomplished peaceful democratic transitions of power, and the latter is starting to reap the benefits of higher oil prices. This is already giving Vlisco a boost in its popular red-and-yellow Yoruba tribal patterns. The key to success seems to be taking the long view: a company that's been around as long as Vlisco has certainly seen the bad times come and go. As V. S. Naipaul put it, "Business never dies in Africa; it is only interrupted."

*